- Home

- Nancy Haddock

Silver Six Crafting Mystery 01 - Basket Case Page 3

Silver Six Crafting Mystery 01 - Basket Case Read online

Page 3

“Nope. Eleanor phoned me directly.” He beeped open his door. “I left another card with her when I was out here Monday evening. I think she has me on speed dial.”

We shared a smile that hung in time and space. I finally looked away, then back.

“Thank you,” I said, and he raised a brow. “I mean for taking a personal interest in my aunt and her housemates. That’s above and beyond.”

“Lilyvale isn’t that big. We look after our own.” He opened his car door, then glanced back at me. “But never doubt I have a job to do, Nixy. Protecting the public includes protecting people from themselves. Remember that.”

Chapter Three

ERIC SHOAR HAD PROVED FRIENDLIER THAN I’D imagined he’d be, was for sure handsome, and oh my, his deep, dreamy drawl was more potent in person. However, his cop stare left no doubt where he’d draw the line. A line I wasn’t eager to cross.

As he drove away, I checked my mental to-do list: Get my aunt and her friends to spill about the explosions and kitchen fires. Observe the mental and physical condition of the Silver Six, especially Aunt Sherry. Discover who Hellspawn was and what she wanted. Hopefully I’d have answers by tonight. Scratch that. I would have answers by tonight. I didn’t have time for Sherry to stonewall me.

Besides, I mused after I snagged my wallet and cell phone from the car and headed back to the porch, Sherry should be tired enough tonight to give me straight answers. Every problem had a solution; every challenge could be overcome. The sooner I had the scoop, the sooner I’d sort things out and be home in Houston. We’d all go back to our normal lives, except that I’d keep closer tabs on Aunt Sherry in the future. Just in case she needed me.

I reached the porch to find she’d clipped her bangs back with the barrette again and was merrily chatting with several customers. It took a moment for her to see me, and when she did, emotion flashed in her eyes. Distress? Panic? Okay, I should’ve called to tell her I was coming. My mother had taught me better manners. But catching Sherry off guard was the point if I wanted to get to the truth and keep her and her housemates from winding up in court.

“I’m fine right now, but I’ll take a break later,” she said after I bagged a bread basket of woven white oak for a customer. “Go enjoy the festival for a bit. Stretch your legs before I put you to work.”

She waved me away as more customers approached, but I didn’t leave. No, she seemed too eager to run me off, so I stood at the porch railing, pulled out my phone, and began to take pictures while surreptitiously eavesdropping. I didn’t overhear anything important, and soon was looking more than listening.

The first detail I noticed suggested that Sherry and her friends kept the property in excellent repair. The porch looked more or less recently painted, and so did the house itself. A lone crepe myrtle sapling about six feet tall stood near the first of the booths, mulch surrounding its base. Mulch-covered flower beds lining the porch teemed with iris blooms, the old-fashioned purple bearded iris my mother had grown. I recognized what my mom had called pinks, too, but couldn’t name the white-flowered ground cover. Sherry’s four forsythia bushes with their bright yellow flowers anchored each end of the beds. My mom had loved forsythia, too.

I gazed beyond the cars and booths to the far side of the yard and the thicket of pines and pin oaks interspersed with redbuds and dogwoods that defined the southern property line. Sherry’s farmhouse sat on a half square block of land, and the miniforest ran along the back of the house and on part of the north side, too. I remembered that from the many photos Sherry had sent, all labeled to give me the feeling of being here. And while I did recognize the general layout of the yard and garden, moving in a space was always a different experience from seeing it in pictures.

“Nixy? Nixy, are you all right?”

I blinked at Sherry’s upturned face. “I’m fine.”

“You were a million miles away, child.”

“I was thinking about how Mom used to talk about this place. You want a break now?”

“Not yet. Go shop. Buy that nice boss of yours a little gift.”

Nice boss? Barbra? I managed not to grimace, but with nothing else to do, I took Sherry’s suggestion to browse.

All art holds value to me, be it fine, folk, or way out there. One of my majors was in fine art, but I only squeaked through. Why? Because I can barely draw a recognizable stick figure. An eye for arrangement, for design, is more my thing, and I used that talent at the gallery to showcase the works of those who have true artistic gifts.

According to one of my professors, folk art was originally created from whatever natural materials were at hand, and esthetics took a distant second to function. Baskets were made for gathering food, gourds for carrying water, and the prettiest of aprons doubled for dust rags in a pinch. But folk artisans had long blended beauty with practicality, and as I strolled through the festival, that truth slammed home. In fact, the high quality of craftsmanship blurred the lines between fine and folk art at every turn.

The horde of shoppers must’ve felt the same way.

I drifted from display to display, snapping photos with my cell phone, astounded by the variety of items. Made of every kind of material from fabric to wood, clay to metal, artists offered quilts, furniture pieces, birdhouses, wall hangings, multimedia paintings, jewelry, and more. Very few vendors repeated goods, and when they did, the prices were comparable. No undercutting one another here.

In chatting up the several dozen artists manning their stations, I noticed distinct trends. That is, aside from the Southern drawls and Southern hospitality I found at each stop.

The first trend was that the artists were in their fifties and older. Second, they all lived in the area. Third, they’d all been doing this festival since Sherry started it three years earlier. Last, and most telling, they all sold their art for one driving reason: to supplement their limited incomes. Unlike other art and crafts festivals I shopped, not one vendor handed out business cards or directed shoppers to their websites for Internet sales. No one took special orders. The artists clearly loved creating their works of folk art, but none of them wanted to invest the time or money to run a web sales operation. Whatever customers wanted had to be bought today, or they were out of luck until the fall festival.

Were Sherry and her housemates supplementing their incomes out of necessity, too? Were any or all of them in financial trouble?

I searched my memory for the facts Sherry had dropped about her housemates in her letters. I knew each of the Six was retired, although I didn’t know what fields they had worked in. Well, except that Sherry had taught school, and Maise had been a nurse. I knew they were all over sixty-five, too, so it was a safe bet they were each getting social security benefits. Sherry may have a retirement fund or pension through the school system, and some of the others might have pensions, too. Of course, that was no guarantee any of them pulled in much monthly income.

As for coming to live with Sherry, Maise and Aster’s home had burned, I recalled. They’d stayed with Sherry as a stopgap, then the three decided to share the farmhouse. The arrangement gave Sherry companionship and security so she wasn’t ambling around the large farmhouse alone. Eleanor came to live with Sherry next. I dredged up something said about an evil landlord. On the circumstance of Fred and Dab joining the ladies, I drew a blank, but Sherry had happily quoted the more the merrier adage. Simple logic dictated that the housemates pooled their financial resources, too.

If the Six did need extra money, even mad money, I needed to do my part.

With that in mind, I sought out Aster’s booth on the south side of the farmhouse. Aptly named Aster’s Aromatics, her setup stood in front of a large garden of plants I couldn’t begin to name, and her tables overflowed with herbal everything—soaps, bath salts, lotions, eye packs, teas. No wonder Aster smelled of herbs. Maise manned the booth with her sister, and they put on a show of being delighted to educ

ate me about the properties of herbs and aromatherapy in general. Still, I felt an odd undercurrent as I selected soaps and lotions for my boss and friends at the gallery. Hard to pin down, but a distinctly different energy from their cheerful welcome when we met on the porch.

Across the way from Aster and Maise, I located Eleanor and Dab presiding over tables featuring carved wood art. Human, animal, plant; and free-form figures; wall art; boxes; boats; and more drew buyers. Some figures were executed with amazing detail; others were more representative. None were painted, and the gorgeous natural wood grains took my breath.

I fell for exquisite napkin rings with a lily motif and bought a set of eight for my roommate Vicki’s wedding gift. Which reminded me. With Vicki leaving, I needed to get serious about apartment hunting. Soon. I couldn’t swing our two-bedroom place solo, not without touching the nest egg my mother had left me. I wasn’t about to deplete those savings unless I invested in buying a place of my own.

Eleanor treated me cordially if a bit coolly, even after I bought the napkin rings. Then again, I sensed a natural reserve from her. Dab acted jovial, but I felt the key there was acted. That, or I was being paranoid and the housemates were simply interested in selling instead of gabbing. Made sense if they had money worries.

Or did they resent me for waiting so long to come visit?

Or resent me for visiting now?

I sighed and reached the backyard as a group of musicians launched into a lively bluegrass tune. No stage for these performers. They stood in the mown grass, the miniforest of trees the backdrop. With fiddles, guitars, banjos, basses, and mandolins they played and smiled at the crowd. Young children pushed closer to dance to the music.

After toe-tapping to two numbers, I went to investigate Fred’s display. He didn’t have a mere table or three. He had a whole shed that stood opposite the farmhouse back porch and deck. The shed’s double doors were thrown open and a banner overhead read FIX-IT FRED: BEST MECHANIC ANYWHERE, I FIX ANYTHING. The shelves inside held small appliances like electric griddles, blenders, and a waffle iron I’d swear had been new in 1960. He also had a few old suitcase-style record players and vintage radios.

Fred himself sat on a tractor-seat stool at a wooden workbench marred with pits and scars. Glasses perched halfway down his nose, he tinkered with a toaster as I approached. Even now, using fine motor skills, the muscles of his upper and lower arms subtly flexed. No wonder, considering the loaded walker he lunged around.

“Mind if I take a peek inside?” I asked when he noticed me.

“Look all you like, but ain’t nothin’ for sale in there. Owners haven’t picked them up yet.”

“Not even that stand mixer?” I eyed the white KitchenAid that had to date from the 1970s.

“It’s a beaut, ain’t it? Lady who owns that still has all the attachments. She’s visitin’ her daughter for a spell.” He gave me narrow glance. “You cook? Bake?”

“Not much, but that mixer is a classic. It’s great that you can fix it.”

“Lotta classics around here, but it don’t mean they’re disposable.”

I met his serious, faintly warning gaze, and knew he spoke of more than household appliances.

“Fred,” a voice called, and I lost my chance to say more.

As I poked around in the shed, I overheard Fred consult with customer after customer about their lawn mowers, tractors, cars, and appliances needing repair. I’d about tuned out the conversations when one caught my ear.

“You better fix that stove in y’all’s own house, Fred. Maybe you wouldn’t have smoke pouring out the windows ever’ other durned day.”

I edged closer to eavesdrop, but stayed out of sight.

Fred humphed. “Stove’s not the problem, Bob. It’s Maise. She’s a helluva cook, but she don’t know ‘come here’ from ‘sic ’em’ about making fancy desserts.”

“What kinda desserts?” Bob asked, emphasizing the “de” in desserts.

“The woman’s obsessed with lightin’ fruit on fire. Pours good liquor over it, flicks that long barbeque lighter, and whoosh.”

“What fool kind of thing is she trying to make?”

“She calls it flambé but it always goes flambooey. She’s too stubborn to quit, though. Says she won’t give up until she gets the dish right.”

I heard the man chuckle. “Well, we’re just across the road, you know. Can see your place easy from the kitchen window. You have our number, right?”

“We do,” Fred confirmed.

“Then holler if you ever need us.”

Fred greeted someone new, and I slipped away from his shed, considering what I’d heard. Igniting booze certainly explained the kitchen fires, but not so much the explosions. Not unless Maise was the mad scientist of cooks.

Hmm. Bob had to live in the subdivision across the way, one that looked to date from the 1970s. A drainage ditch, then a brick wall separated the neighborhood from the road. I recalled seeing it as I followed Detective Shoar. I’d lay odds Bob was one of the complaining neighbors, but he wasn’t testy with Fred. That was good.

I blinked, realizing I’d been staring into space again, and looked around. Three vehicles were parked off to my left near the fence—a rather beat-up red pickup, a blue Corolla, and a dark gray Cadillac. The Corolla was Sherry’s. I remembered her driving it when my mom died. Also on the left, some ten yards from Fred’s shed, were two country-red outbuildings a little wider and deeper than single-car garages, and beyond those a barn the same color. Not a ginormous barn, but with typical high double doors. I startled when a standard-sized side door swung open. A harried woman about my age hustled out, shooing two children in front of her. I was a second from confronting her for being in a nonpublic area when I noticed the RESTROOM sign beside the door.

It seemed beyond progressive to have a bathroom in the barn, but it made sense for the festival. On-site facilities kept customers on the grounds ready to spend more money, yet renting porta potties would cut into the profit margin. Toilet paper, paper towels, and soap were cheap by comparison.

The woman and her children hustled away, but I spotted someone else skulking by the back of the barn. I blinked, squinted, whipped out my cell to take a picture. She’d covered her blonde hair with a blue ball cap but hadn’t changed from the jeans and summer sweater she’d worn earlier. The one that enhanced her Dolly Parton chest.

Shoot fire. If Hellspawn’s minion was here, was Hellspawn herself far behind?

Detective Shoar had been wrong about the troublemakers staying away, but I’d routed them once, and I’d do it again.

The minion peered out from behind the corner of the barn, spied me, and gave me a come here wave, but I was already on the move.

Chapter Four

I STOMPED THROUGH THE MOWED FIELD GRASS TO where the woman stood at the corner of the barn.

“What are you doing back here?” I demanded.

“Finding you.” Coming from a tall, big-boned gal who looked like she could snap me in half, her breathy voice startled me. Deep but breathy. Like Marlene Dietrich doing Marilyn Monroe, and yes, I’d dated an old-movie buff.

The minion craned her neck, her gaze darting from me to the main yard and back. “I’m Trudy Henry.”

“What do you want, Trudy?”

She hesitated, bit her lip, and again scanned the area as if looking for spies. “I want to buy one of your aunt’s white oak baskets. One with the rope handle braided in with blue gingham fabric. I have money.”

She wedged a fat roll of twenties from her jeans pocket, and I couldn’t help but stare.

“Your boss pays you big bucks, huh?”

Trudy made a sour face. “This is from my savings. May I buy a basket?”

Sincere as she sounded, I shook my head. “I don’t think it’s a good idea to come back to the festival today.”

Her shoulders slu

mped. “Can I buy one later if your aunt has any left over?”

“I’ll ask her for you,” I said more kindly. The girl was about my age but reminded me of an awkward puppy. “Is that all you wanted?”

“Actually, no. I need to warn you about Ms. Elsman. I’m not supposed to talk about her business, but you need to know she’s, uh, pretty determined to get, ah, what she wants.”

I stiffened. “Which is what?”

“You need to ask your aunt about that. Like I said, I shouldn’t be talking to you at all, but I’m worried about how far Ms. Elsman will go.” Trudy looked close to tears. “I just don’t want anyone to get hurt. Please, talk with your aunt.”

With a wave, Trudy galumphed off toward the back of Sherry’s property and disappeared into the woods that extended to the next street over. In spite of not having visited Sherry before now, I had listened when my mother talked about playing hide-and-seek out behind the house. She’d mentioned her old home often in the weeks before her stroke, had longed to visit again. Then it had been too late to bring her.

It wasn’t too late to help Sherry. Trudy’s warning worried me even more than the kitchen fires, and my resolve to get these mysteries sorted out doubled.

I spent the rest of the morning selling handwoven baskets to a steady flow of festival customers. Sometimes Sherry stayed with me for a spell. More often I manned the wares without her, although she flitted back to check on sales or to introduce me to groups of people. I met two women who had taught with Sherry at the junior high school and three others about my age who had been Sherry’s students. A former-student fireman and four city and county bigwigs stopped by, too.

The young women didn’t shop Sherry’s baskets. They flirted with Ben Berryhill, a tall, muscles-on-muscles fireman, and with the equally tall Bryan Hardy, introduced to me as the county’s deputy prosecuting attorney. Though I kept expecting Ben to mention Sherry’s kitchen fires, he never did. Bryan Hardy’s baby face belied the age he had to be to have finished law school, practiced law, I presumed, and now hold an important office. His black-framed glasses made his face look even broader and younger, but he also seemed quiet, almost shy for a guy in his position. The Houston attorneys I’d dated had been more flash and brash, and I found myself liking Bryan’s hazel eyes and soft-spoken voice. What little I heard of his voice.

Last Vampire Standing

Last Vampire Standing A Crime of Poison

A Crime of Poison La Vida Vampire

La Vida Vampire Silver Six Crafting Mystery 01 - Basket Case

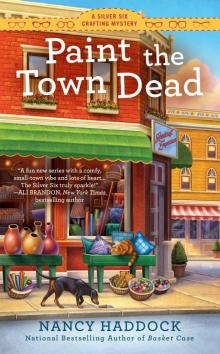

Silver Six Crafting Mystery 01 - Basket Case Paint the Town Dead

Paint the Town Dead Always the Vampire

Always the Vampire